What Signals That Act Within The Animal Body Are Produced By Endocrine Glands?

Learning Objectives

- Identify the major glands and body structures involved in hormone synthesis in vertebrates

- Recall the functions of selected hormones produced by select major glands

- Draw the hormone pathway in given examples, including claret glucose, hunger, metamorphosis, stress, and/or sex activity, and make predictions on how an animal would respond to given stimuli for each example

- Recognize instances of negative feedback loops, positive feedback loops, and crosstalk in the instance hormone pathways

Vertebrate Endocrine Glands and Hormones

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biology 37.5

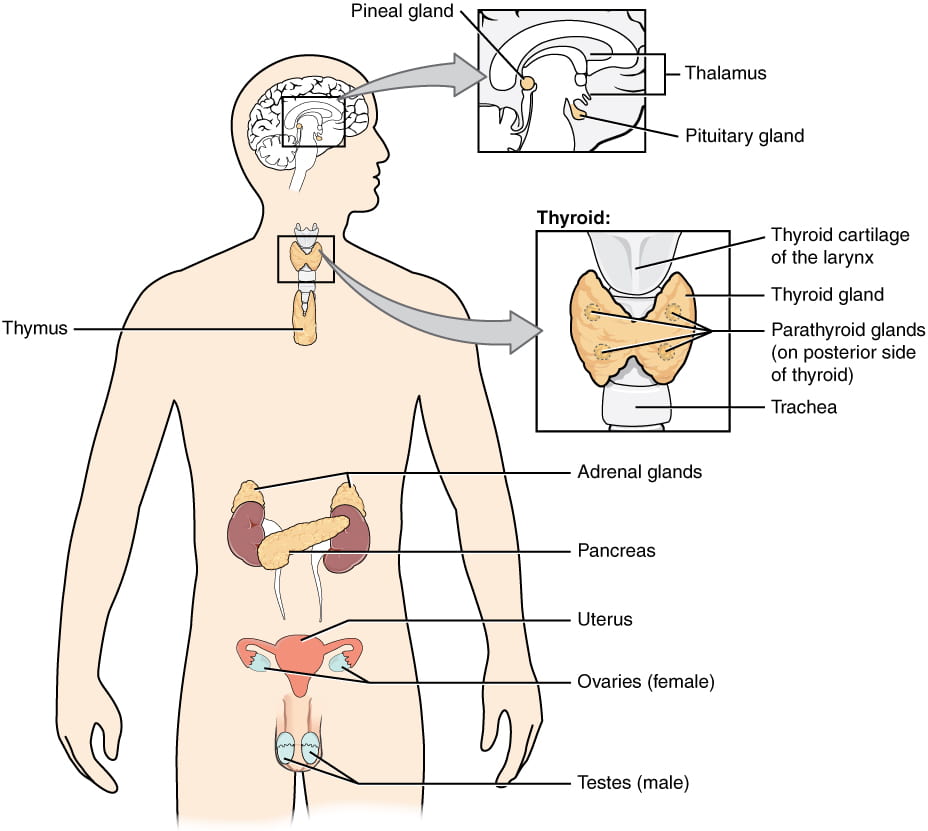

Unlike plant hormones, creature hormones are frequently (though non always) produced in specialized hormone-synthesizing glands (shown below). The hormones are then secreted from the glands into the blood stream, where they are transported throughout the body. There are many glands and hormones in different beast species, and nosotros will focus on but a small-scale collection of them.

Locations of endocrine glands in the man body. Prototype credit: OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology.

In vertebrates, glands and hormones they produce include (note that the post-obit list is not complete):

- hypothalamus: integrates the endocrine and nervous systems; receives input from the trunk and other brain areas and initiates endocrine responses to ecology changes; synthesizes hormones which are stored in the posterior pituitary gland; as well synthesizes and secretes regulatory hormones that control the endocrine cells in the anterior pituitary gland. Hormones produced include

- growth-hormone releasing hormone: stimulates release of growth hormone (GH) from the inductive pituitary

- corticotropin-releasing hormone: stimulates release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the anterior pituitary

- thyrotropin-releasing hormone: stimulates release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) from the inductive pituitary

- gonadotropin-releasing hormone: stimulates release offollicle -stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone from the anterior pituitary

- antidiuretic hormone (vasopressin): promotes reabsorption of h2o by kidneys; stored in posterior pituitary

- oxytocin: induces uterine contractions labor and milk release from mammary glands; stored in posterior pituitary

- pituitary gland: the torso's master gland; located at the base of the brain and attached to the hypothalamus via a stalk called the pituitary stalk; has 2 distinct regions: the inductive portion of the pituitary gland is regulated by releasing or release-inhibiting hormones produced by the hypothalamus, and the posterior pituitary receives signals via neurosecretory cells to release hormones produced past the hypothalamus. Hormones produced (or secreted) by the gland include:

- anterior pituitary: the post-obit hormones areproduced by the inductive pituitary and released in response to hormone signals from the hypothalamus

- growth hormone: stimulates growth factors

- adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH): simulates adrenal glands to secrete glucocorticoids such as cortisol

- thyroid-stimulating hormone: stimulates thyroid gland to secrete thyroid hormones

- follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)andluteinizing hormone (LH): stimulates production of gametes and sex steroid hormones

- prolactin: stimulates mammary gland growth and milk product

- posterior pituitary: the following hormones areproducedpast the hypothalamus andstored in the posterior pituitary

- antidiuretic hormone: promotes reabsorption of water by kidneys; stored in posterior pituitary

- oxytocin: induces uterine contractions during labor and milk release from mammary glands during suckling; stored in posterior pituitary

- anterior pituitary: the post-obit hormones areproduced by the inductive pituitary and released in response to hormone signals from the hypothalamus

- thyroid gland: butterfly-shaped gland located in the neck; regulated past the hypothalamus-pituitary centrality; produces hormones involved in regulating metabolism and growth:

- thyroxine (T4) andtriiodothyronine (T3): increment the basal metabolic rate, affect protein synthesis and other metabolic processes, help regulate long bone growth (synergy with growth hormone)

- adrenal glands: two glands, each located on one kidney; consist of adrenal cortex (outer layer) and adrenal medulla (inner layer), which each produce dissimilar sets of hormones:

- adrenal cortex:

- mineralocorticoids, such as aldosterone:increases reabsorption of sodium by kidneys to regulate water balance

- glucocorticoids, such every bit cortisol and related hormones: long-term stress response hormones that increase blood glucose levels by stimulating synthesis of glucose and gluconeogenesis (converting a non-saccharide to glucose) by liver cells; promote the release of fat acids from adipose tissue

- adrenal medulla:

- epinephrine (adrenaline)andnorepinephrine (noradrenaline): brusk-term stress response ("fight-or-flying") hormones that increase heart rate, breathing rate, cardiac muscle contractions, blood force per unit area, and claret glucose levels; accelerate the breakup of glucose in skeletal muscles and stored fats in adipose tissue; release of epinephrine and norepinephrine is stimulated directly by neural impulses from the sympathetic nervous system

- adrenal cortex:

- pancreas: located between the tum and the proximal portion of the small intestine; regulates claret glucose levels via the hormones:

- insulin: decreases blood glucose levels by promoting uptake of glucose past liver and musculus cells and conversion to glycogen (a sugar storage molecule)

- glucagon: increases blood glucose levels by promoting breakdown of glycogen and release of glucose from the liver and muscle

- gonads: produce sex steroid hormones that promote development of secondary sex characteristics and regulation of gonad function:

- ovaries(in females):

- estradiol: regulates development and maintenance of ovarian and menstrual cycles

- progesterone: prepares uterus for pregnancy

- testes (in males): regulates evolution and maintenance of sperm production

- ovaries(in females):

The hormones produced and/or stored by the pituitary gland are summarized here:

Modification of work by OpenStax College – Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions Web site. http://cnx.org/content/col11496/one.half dozen/, Jun 19, 2013., CC By 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/west/alphabetize.php?curid=30148147

This video provides a nice overview of the glands and hormones of the vertebrate endocrine system:

Hormonal Regulation of Body Processes in Animals

The information below was adapted from OpenStax Biological science 37.3

Hormones have a wide range of effects and modulate many different trunk processes. The primal regulatory processes that volition be examined hither are those affecting blood glucose, hunger, metamorphosis, stress, and sex. We will primarily focus on these processes in vertebrates, but will also consider invertebrates in some cases.

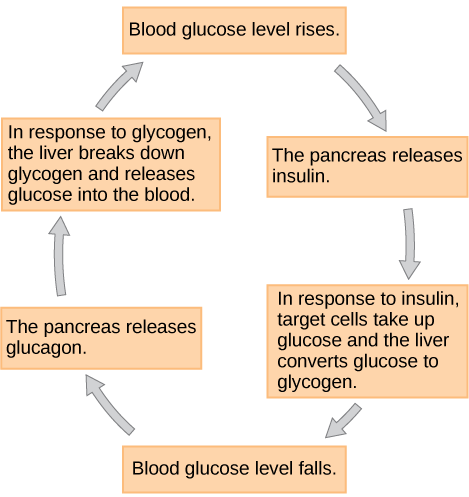

Claret Glucose

Glucose is the principal energy source for well-nigh animal cells, and it is distributed throughout the body via the blood stream. The ideal, or target, blood glucose concentration is well-nigh 90 mg/100 mL of blood, which equates to nearly i tsp of glucose per 6 quarts of blood. After a repast, carbohydrates are cleaved down during digestion and absorbed into the blood stream. The amount present following a meal is typically more than what the body needs at that moment, and so the extra glucose must be removed and stored for subsequently apply. The reverse phenomenon occurs post-obit a period of fasting.Insulin and glucagon are the two hormones primarily responsible for maintaining advisable blood glucose levels.

Insulin is produced by the beta cells of the pancreas, which are stimulated to release insulin every bit blood glucose levels ascension (for case, after a meal is consumed). Insulin lowers blood glucose levels through several processes:

- enhances the rate of glucose uptake and utilization by target cells, which use glucose for ATP product

- stimulates the liver to convert glucose to glycogen, which is and so stored by cells for later use

- increases glucose transport into certain cells, such every bit muscle cells and the liver

- stimulates the conversion of glucose to fatty in adipocytes and the synthesis of proteins.

These deportment together cause cause claret glucose concentrations to fall, chosen a hypoglycemic 'low sugar' result, which inhibits further insulin release from beta cells through a negative feedback loop.

When claret glucose levels decline beneath normal levels, for example between meals or when glucose is utilized rapidly during practise, the hormone glucagon is released from the alpha cells of the pancreas. Glucagon raises blood glucose levels, eliciting what is called a hyperglycemic effect through several mechanisms:

- stimulates the breakdown and release of glucose from glycogen in skeletal muscle cells and liver cells

- stimulates absorption of amino acids from the blood past the liver, which then converts them to glucose

- stimulates adipose cells to release fatty acids into the blood

Glucose can then exist utilized as energy by muscle cells and released into apportionment by the liver cells. These actions mediated by glucagon result in an increase in blood glucose levels to normal homeostatic levels. Rise blood glucose levels inhibit further glucagon release past the pancreas via a negative feedback mechanism. In this way, insulin and glucagon work together to maintain homeostatic glucose levels, as shown in below.

Insulin and glucagon regulate blood glucose levels. When blood glucose levels fall, the pancreas secretes the hormone glucagon. Glucagon causes the liver to break downwards glycogen, releasing glucose into the blood. As a result, blood glucose levels rise. In response to high glucose levels, the pancreas releases insulin. In response to insulin, target cells accept up glucose, and the liver converts glucose to glycogen. Equally a event, blood glucose levels fall. Epitome credit: OpenStax Biology

Hunger Direction

The firsthand form of energy for most animal cells is glucose, and extra glucose is stored equally glycogen which is readily broken downward into glucose when needed. Longer term reserves of energy are stored every bit fats, in cells called adipocytes. Too picayune fat ways at that place may no exist enough energy reserves in times when food is less bachelor, and will cause an brute to feel hungry; however, also much fat is generally unhealthy and is likely to cause an animate being to feel satisfied. The hormone leptin helps maintain an advisable corporeality of fat reserves in the body.

Rather than being secreted from a specialized gland, leptin is produced by adipocytes in proportion to their number and size. More and larger adiopcytes means more leptin; fewer and smaller adipocytes means less leptin. Leptin levels are detected by sensors in the hypothalamus. High lepin levels suppress ambition and speed up metabolism, while low levels of leptin stimulate hunger and slow downwards metabolism, resulting in a negative feedback loop. These activities are mediated through signaling from the hypothalamus-pituitary axis to the thyroid, which plays a major role in regulating metabolic role.

In response to high levels of leptin, the hypothalamus releases thyrotropin-releasing hormone, signals to the anterior pituitary to release thyroid-stimulating hormone. The thyroid the releasesthyroxine, also known every bit tetraiodothyronine or T4 , and triiodothyronine, also known as Tiii . These hormones affect nearly every cell in the body except for the adult brain, uterus, testes, blood cells, and spleen. Tthree and T4 activate genes involved in free energy production and glucose oxidation, resulting in increased rates of metabolism and body heat production which together cause an increased rate of caloric usage. Low levels of leptin crusade the opposite response, leading to a decreased metabolic rate to conserve energy.

This video describes how the thyroid manages metabolic processes:

Growth and Metamorphosis

In vertebrate species that undergo metamorphosis, such as amphibians, surges of T3 are responsible for initiating development of new structures, reorganization of internal organ systems, and other processes that occur during metamorphosis. In insects, metamorphosis is controlled past a set of hormones that determine whether the animal grows into the next larval stage or changes into an adult as it gets larger. The corpus allatum, an endocrine gland in the brain, secretes a hormone calledjuvenile hormone during all larval stages, which maintains the larval condition of the animal. As the larvae grows, another endocrine gland in the brain releases prothoracicotropic hormone, which signals to the prothoracic gland to release the hormoneecdysone. Ecdysone promotes either molting (shedding the exoskeleton) or metamorphosis, depending on the level of juvenile hormone. Ecdysone in combination with loftier juvenile hormone results in molting into the next larval phase; ecdysone in combination with low juvenile hormone results in metamorphosis into an developed.

Stress: Short vs Long Term Responses

1 of the principal functions of endocrine hormones is to ensure the trunk's internal surround remains stable (homeostasis). Stressors are stimuli that disrupt homeostasis. Some stressors require immediate attention and activate the short term, "fight-or-flight" stress response, which stimulates an increase in energy levels through increased claret glucose levels. This prepares the body for physical action that may be required to respond to stress: to either fight for survival or to abscond from danger. The fight-or-flight response exists in some form in all vertebrates.

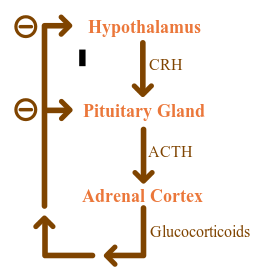

In dissimilarity, some stresses, such as illness or injury, can last for a long time. Glycogen reserves, which provide energy in the brusk-term response to stress, are exhausted after several hours and cannot meet long-term energy needs. If glycogen reserves were the only free energy source available, neural functioning could not be maintained once the reserves became depleted due to the nervous system's high requirement for glucose. In this state of affairs, the body has evolved a response to counter long-term stress through the actions of the glucocorticoids, which ensure that long-term energy requirements can be met. The glucocorticoids mobilize lipid and poly peptide reserves, stimulate gluconeogenesis, conserve glucose for employ by neural tissue, and stimulate the conservation of salts and water.

The sympathetic nervous system regulates the stress response via the hypothalamus. Stressful stimuli cause the hypothalamus to bespeak the adrenal medulla (which mediates short-term stress responses) via nerve impulses, and the adrenal cortex, which mediates long-term stress responses, via the hormone adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which is produced by the inductive pituitary.

Brusk-term Stress Response

When presented with a stressful situation, the torso responds by calling for the release of hormones that provide a burst of energy. The hormones epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) and norepinephrine (as well known as noradrenaline) are released by the adrenal medulla. These 2 hormones set up the body for a burst of energy in the following means:

- cause glycogen to be broken down into glucose and released from liver and musculus cells

- increment blood pressure level

- increase breathing rate

- increment metabolic rate

- change blood flow patterns, leading to increased blood menstruum to skeletal muscles, heart, and brain; and decreased blood flow to digestive system, peel, and kidneys

Long-term Stress Response

Long-term stress response differs essentially from short-term stress response. The torso cannot sustain the bursts of energy mediated by epinephrine and norepinephrine for long times. Instead, other hormones come into play. In a long-term stress response, the hypothalamus triggers the release of ACTH from the anterior pituitary gland. The adrenal cortex is stimulated by ACTH to release steroid hormones called corticosteroids. The 2 main corticosteroids are glucocorticoids such as cortisol, and mineralocorticoids such as aldosterone. These hormones mediate the long-term stress response in the following ways:

- glucocorticoids:

- promote breakdown of fat into fat acids in the adipose tissue and release into bloodstream for ATP production

- stimulate glucose synthesis from fats and proteins to increase blood glucose levels

- inhibit allowed role to conserve energy

- mineralcorticoids:

- promote retention of sodium ions and h2o by kidneys

- increase blood pressure and book (via sodium/water retention)

Coticosteriods are under control of a negative feedback loop (illustrated beneath), which can become mis-regulated in cases of chronic long-term stress.

Diagram of physiologic negative feedback loop for glucocorticoids. Image credit: DRosenbach [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

In contrast to chronic long-term stress, the video below discusses some of the circumstances where stress can be good for you:

Source: https://organismalbio.biosci.gatech.edu/chemical-and-electrical-signals/animal-hormones/

Posted by: gossforproing.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Signals That Act Within The Animal Body Are Produced By Endocrine Glands?"

Post a Comment